Ismoil Somoni, Tajikistan turned into Khan Tengri north, Kyrgyzstan, 2023

At this time last year (first week of August) I was just coming out of 6 weeks in a cast/boot after breaking my right ankle in 2 places in a stupid hiking accident after rock climbing in the Dolomites. So I haven’t been at high altitude since 2021.

The original plan was to climb Ismoil Somoni, one of the five Snow Leopard peaks in the former USSR. Ismoil Somoni and Korzehenvskaya (both are Snow Leopard peaks) are located in the Pamirs of Tajikistan and are adjacent to one another, therefore sharing the same base camp.

I planned my travels so I would be in Istanbul for a week. This way I had a direct flight to Dushanbe, ensuring my gear bags would arrive. This is because Dushanbe only has 2 flights per week from western destinations and if your gear doesn’t make it on your flight, you’re screwed and have to wait several days for it to possibly arrive. You’re also out of luck because Tajikistan doesn’t have the climbing and outdoor gear that we take for granted in the EU and North America. If you lose your double boots, you cannot replace them in Dushanbe. If your -35F sleeping bag disappears in transit, you absolutely cannot find a specialty product like this in Dushanbe. There is no climbing gear to be found in the country. There are also no Tajik climbing guides.

The flight situation from western destinations is likely due to Tajikistan’s close alliance with Russia (plenty of pictures of Emomali Rahmon with Putin around the city and multiple daily flights from Russia). Tajikistan also has a close relationship with China, which is pouring money into roads and buildings around Tajikistan as part of the Belt and Road Initiative. And fun fact, according to Wikipedia and other internet sources, Tajikistan is known as a nepotistic kleptocracy and a large proportion of its GDP is attributed to heroin smuggling from neighboring Afghanistan. The outlook for citizens is not fantastic and four individuals asked Arturo (our guide from Mexico) how to get smuggled into the US via Mexico and its cartel coyotes.

As a side note and in relation to China’s influence, I went to 55 Gym in Dushanbe out of sheer boredom during the time we were stuck there, felt sick from the intense heat (40 degrees Celsius and no air conditioning unless you were in the ladies gym), and noticed that there was facial recognition technology used to enter the workout floor. The facial recognition company? Hikvision, a Chinese surveillance company that has provided cameras for detention centers, mosques, and schools in Xinjiang as part of the suppression of China’s Uyghur population. However, I recognize that we have plenty of issues in the US with surveillance and robodogs, so this isn’t a holier than thou post, just noting how weird it was to have facial recognition technology used at a gym!

Back to arrival. All my gear arrived. And I found Arturo, M (a Czech Google site reliability engineer), and A (a Brit engineer) at the airport. Their gear didn’t arrive. Fuck. It was because they had flown from three different airports in the UK and all were delayed, making their connections through Istanbul a short 30 minutes. So their gear bags and the group gear never made it onto the plane. This was Monday at 3:00 am. We milled around with the other climbers on the flight and tried to find our in-country representative. It used to be Pamir Peaks, but they folded during the pandemic. And now it was Tajik Peaks in collaboration with their Kyrgyz counterparts, Ak-Sai (they’re the biggest outdoor adventure company in Kyrgyzstan). Olga, the Kyrgyz representative from Ak-Sai, was supposed to be at the airport. But Olga was nowhere to be found. There was just a desultory Tajik Peaks representative who didn’t seem to know what was happening. But we finally got all our bags (think two 100 liter duffel bags per person) out the door to the taxi area. But there wasn’t a bus for all of us. So we had to find several taxi drivers to take us to our lodgings. And the drive to the lodgings was…interesting. Apparently no one has to pass a driving test. You can buy a license. So it felt like we were drag racing through the streets of Dushanbe with a driver who texted and barely paid attention to the road. I had the brief thought that this would be one of the more interesting ways to die.

Our lodgings? A business center? But wait! It had an aparthotel on the top floors. We were all exhausted and just wanted to get checked in. But they were so disorganized and didn’t sort out the beds per suite for the number of people in each group. The four of us were assigned to a suite, but it had 2 beds. So we switched with a German brother and sister, who had a suite with 2 bedrooms, 1 sofa bed, and 1 couch. At that point, we said okay and passed out for the night. The next day, we found out that the next flight from Istanbul to bring us our gear bags wouldn’t arrive until 1 am on July 13th. The problem was there were only 3 official dates for the helicopter to leave from Djirgital to go to base camp - July 11, July 28, and August 8. And absolutely no other flights unless we paid $20,000. Availability of helicopters also changed after the 2018 helicopter accident when climbers and flight crew were killed when the helicopter flew down the wrong valley and crashed, killing 5 of 18 people. Additional details from Arturo included the fact that the rear rotor hit first and sent the helicopter into a spin, which spit climbers out the back and into rock and snow. The Tajikistan military couldn’t locate them at first but then there were SOS signals from three Garmin inReach mini satellite devices (I have one for expeditions as well) that helped pinpoint climbers. However, it took 2 days for everyone to be rescued. Further complicating matters, the president’s family purchased the helicopter and it’s operated under Somon Air. Add to that a shortage of pilots. So there went the whole season for Tajikistan despite good planning on my part.

Waiting to collect the delayed gear bags. A gave it a 10% chance of all the bags arriving. To our surprise, everything did show up! We arrived at 1:00 am and collected everything by 3:00 am. Talk about mucked up hours. Also? Dushanbe airport is tiny. Its saving grace is it was more organized than Almaty airpor. Almaty airport is one I will characterize as the worst airport and biggest dumpster fire I’ve passed through - from the complete chaos and lack of queuing at passport control, the hourlong wait to clear passport control after line hopping into the Kazakh citizen’s lane, to hopping the baggage conveyor belt to help Japanese tourists get backpacks that had gotten stuck and fallen inside the U.

I had the option of climbing with a private guide in Tajikistan and in retrospect, I am kicking myself for the lost opportunity. In hindsight I should have dumped the group and gone to Tajikistan, but I was worried about 3 things . 1) Food supplies. Without our dehydrated food, I knew the quality and quantity of food would be an issue at higher camps, and that always adds to the debilitation of altitude. 2) I didn’t know what I would get into with a Russian or Kyrgyz guide whom I didn’t know and I was assuming that Arturo would be a semi-decent guide considering A had climbed with Adventure Peaks for the last decade+. 3) Safety in numbers. It’s usually better to go with three members in a party and going down to two also meant the load carrying would be worse with less people to split tent/food/fuel/gear across. And I’m not a big and young man so I have to be realistic about using porters and how much I can carry. I have carried up to 40-45 pounds at altitude. It sucks. This was not the year to do it considering coming off of a broken ankle the year before and not having spent any significant time at altitude before this trip.

But little did I know that Arturo was going to be as incompetent and shitty a guide as he turned out to be. But I did jump at the chance for a first look at Khan Tengri from the north side, a mountain I had wanted to try in 2021 but didn’t get to attempt then. So I ended up sticking with the group for five days in Dushanbe while we waited for gear bags and decided to go to Kyrgyzstan in an attempt to salvage the season. Thankfully a friend knew a USAID coworker based in Dushanbe, so I got to hang out with Lu for two nights and that was a welcome break from the guys. I was bored with sitting around the hotel all day. I can understand A’s fretting because he has been trying to become the first Brit to snag the Snow Leopard award but has been shut down in Tajikistan for the past 4 years. He has climbed Korzhenevskaya but trying to get to Ismoil Somoni has been difficult. He flew to Dushanbe in 2019 but couldn’t get on the helicopter. In 2020-2021 the pandemic shut things down. In 2022 he was unable to get a visa. And now 2023 was a wash. He’s also been in Kyrgyzstan a dozen times now, having climbed Pik Lenin and Khan Tengri, among other things.

So after we recovered the gear bags. It was off to Kyrgyzstan on a Friday. But because Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan have an ongoing border conflict that resulted in some deaths in the fall of 2022, there are no direct flights and border crossings by land have been shut down. So we had to fly northeast to Almaty (where we had a 2-hour delay) to fly southwest to Bishkek. We were in Bishkek for a few days sorting out things and buying groceries. Then we drove 8 hours east to Karkara, the staging point for the helicopter to Khan Tengri north and Khan Tengri south/Pik Pobeda base camps. Our ride was a 1960s era military helicopter and it doesn’t fly to both camps every day. Some days it goes to the north. Some days to the south. Some days it doesn’t fly at all. And the weather dictates when it can fly.

We were also sent off with an “everyone stay alive” comment from the camp manager, which I think should be on a t-shirt for anyone who climbs in this region. Khan Tengri - Everyone Stay Alive. Pik Pobeda - Everyone Stay Alive! Especially Pik Pobeda (Russian for “Victory”) considering climbers die on it every season (four this season - the assumption is that it was an avalanche that killed them after they summited). In fact, Nastiya (the country’s only female IFMGA guide as well as a Snow Leopard award recipient. She was also my guide on Pik Lenin in 2021) and Carla Perez (an Ecuadorian friend who is an IFMGA guide, climber, and the first LatAm woman to summit Everest and K2 without supplemental oxygen) are two women I know who have climbed Pik Pobeda and they both reported that it was extremely difficult. Nastiya noted that they were constantly digging their snow cave deeper into the snow because of constant avalanches on the route. There’s also a 7-mile long knife-edge ridge (at about 6000 masl) on Pik Pobeda where the fickle weather can change and blow you off the mountain and to your death in China or in Kyrgyzstan, depending on the direction the winds come from. Oh, and since A had climbed Khan Tengri before, he wanted to get a first look at Pik Pobeda. As it turns out, his misadventures continued and his guide fell 45 feet to the near bottom of a crevasse near camp 1 on Pobeda. Fucking terrifying.

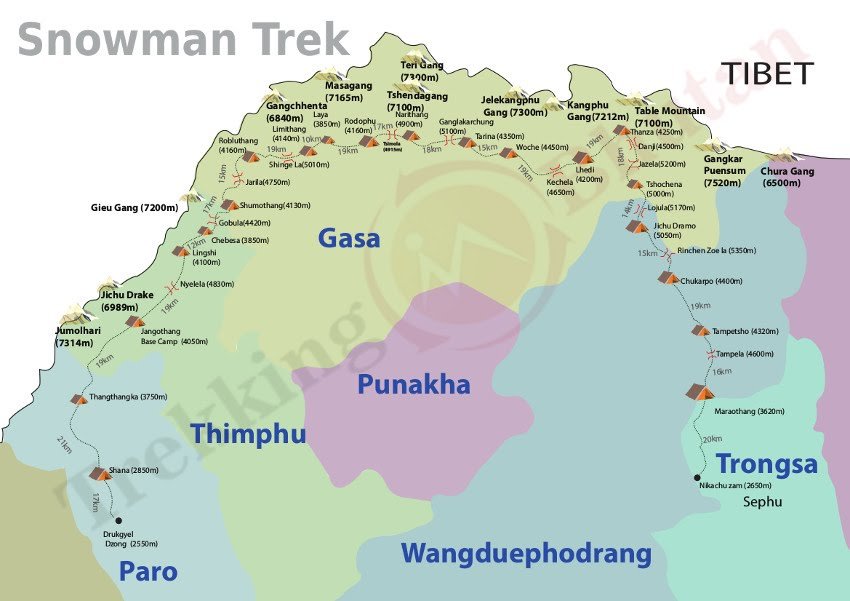

About Khan Tengri. It’s considered the second most difficult and technical of the Snow Leopard peaks. There are two options to climb it. From the north and from the south. The north is considered safer from avalanches and serac collapse, but it’s more technical and steep and requires fixed ropes for the majority of the route. It requires ascending to camp 1 (~4500 masl), then a 1000 meter ascent to camp 2 (~5500 masl), summiting Chapayev Peak (6100 masl) plus a descent of 300 meters to camp 3 (5800 masl), and then a long summit ascent to 7010 masl. The south is technically easier and fixed ropes don’t come into play until you attempt the summit. However, the route passes through significant avalanche and serac collapse danger, which has killed climbers in the past. Some companies don’t run trips on the south side for that reason. Also note that the south side base camp is shared with climbers attempting nearby Pik Pobeda.

Below you’ll see some videos and photos from our time there.

Arriving at Khan Tengri north base camp on the 19th of July. About a 40 minute flight from Karkara. And yes, there was an open window and I was hanging my phone out the window during the flight.

Inside of the helicopter. I know my aerospace/astrophysics engineering friend had a good hard look at the wires in the upper left. I don’t think I want to know what he thought considering the fact the helicopter had to turn around halfway because of engine oil issues on one trip, and it was in Bishkek another time for maintenance. All this season alone.

Dropping us off. They don’t power down the helicopter during dropoff/pickup, so beware the rotors. They load/unload as fast as possible. And because of the shape of the valley, the helicopter has to execute this midair turnaround. The wash is pretty intense. Also, a small human moment I noticed was when the pilot would give Dmitri, the camp manager, hand picked flowers from around Karkara. These flowers were for the base camp chef.

View towards the east and China. To the left we were technically in Kazakhstan. And on the mountain we were in Kyrgyzstan.

Base camp toilets. As the glacier melted during the season, these became interestingly unstable. One day I got in one of the toilet stalls only to find it swaying back and forth. I thought I was going to end up in the crap crevasse with the added indignity of getting tetanus. Thankfully it didn’t fall over and they eventually moved it so it was on more stable glacier.

Base camp “shower/sauna”. The best feeling if you’ve been on the mountain for a few days. Until you want to pass out from the heat. Also make sure you get the proper mix of hot and cold water because you can scald yourself. It’s also possible to attempt to do laundry. If you’ve ever had to wear sweat soaked socks that have dried x 4-5 days in a row, you know it feels disgusting. Any opportunity to clean up is welcome.

The young men at work. The staff consisted of several young men in their late teens and early twenties. There aren’t many jobs in the region, I suppose. I can’t imagine US kids doing this kind of work. Also, these are the mats that we slept on at base camp. I didn’t think too much about the hygiene factor.

The precariously balanced hand washing station. It had to be moved eventually because it was like a ship swaying on a precariously balanced piece of glacier.

Laundry day. Drying clothes can be a challenge, especially at higher camps. Trying to dry clothes out in the sleeping bag at night is a mixed affair. It usually doesn’t dry out, but it does keep it from freezing. So I usually had a lot of clothing in my sleeping bag. But the sweat soaked socks at camp 2 were too gross and I had to toss them out of my bag in the middle of the night.

Russian style breakfast gruel. Aka gulag cereal. This is not Argentina or Nepal or anywhere else I’ve climbed where operators provided enough good quality food with sufficient calories. Other climbers who booked with Ak-Sai grumbled about the logistics, communication, and quality of food. Which was one of my concerns if I had abandoned the group in Tajikistan to climb with a private guide, but without the freeze-dried meals from the UK. Note that at altitude, it’s not uncommon to burn through 6000-10,000 calories in a given day between the altitude, hypoxia, and exertion. Keeping your weight stable through an expedition is a skill in itself and weight loss is inevitable for most people. We definitely had a few long days where we didn’t have breakfast and climbed for hours without any substantial food.

The dining tent expanded and grew more unsteady with time. Keeping soup and drinks from spilling was an exercise in futility based on how much the platform moved. Here you can see how precariously it was positioned on the melting glacier.

The glacier near base camp. Don’t be fooled. If you fall in, you’re screwed. A climber died a few years ago after falling in and drowning. Some of the rivers in the glacier tunnel underneath the glacier.

First look at Khan Tengri north. It doesn’t look so bad from here, but imagine a a barely visible black speck on this mountain and you’ll get an idea of the scale. Also note that the right side is the ascent up to Chapayev Peak. From the base of the mountain, you have to zigzag around looking for the start of the fixed rope and then attach your ascender and start heading up. Above camp 1 you have to ascend by the ridgeline, which is towards the middle of the picture. Steep on both sides! And you have to ascend a whole other mountain to get to the saddle to try a summit on Khan Tengri (left). This is what you have to do on most of the other Snow Leopard Peaks. These are all big and intimidating mountains.

The avalanche debris on the way to camp 1. I saw this slide multiple times and yeah, it goes right into the crevasse.

M and I heading up the last 15-20 minute to camp 1.

View near the slide and on the way up to camp 1.

View from camp 1. This is from the area I dubbed “poop rocks”. It’s where you finish climbing into camp 1 and it’s also below the area where you set up tents. Camp 1 has limited space for tents and there’s limited privacy to go to the bathroom. So here we are. The human waste problem gets worse as the season progresses. But if you know this trick, you can help keep it clean - do your business on a big flat rock and chuck it over the cliff to the right! But don’t have too much of a back swing.

About 3 hours above base camp. You can see how far camp 1 is from this point (look hard for the yellow specks in the distance). And you get a better view of the ridge we had to ascend. Camp 1 to camp 2 is a grueling and steep ascent of 1000 meters. It sucked and was painful. And this was our half-assed acclimatization day where we only went to 5100 masl and not to camp 2. Also, this kind of terrain doesn’t really allow you to rest, eat, drink, or apply sunscreen.

M about 3 hours above camp 1. I’d say my strength is that I have a high comfort level with scraping my crampons around on rock after spending the last 3 seasons climbing in Ouray and Canmore and working on ice/mixed/drytooling skills. Thank you Sean Isaac for teaching us how to scratch around on rock during the mixed climbing camp in January!

Some of the rocks 3 hours above camp 1. Always a fun game of 1) am I clipped in correctly and 2) which rope is the newest? Clipping into an old rope could mean a nasty and deadly fall of thousands of feet. Also, huge kudos to the amazing rope fixing team responsible for setting up over 2000 meters of fixed rope up the north side! Also, because of Arturo’s poor decision making with caching gear before camp 1 and in an avalanche path, we lost a week’s worth of food and fuel, a shovel, and my down gloves. And so we ended up not being able to acclimatize properly by going up to camp 2. This basically ensured we were screwed for any summit attempt. We had the time to do a proper acclimatization and load carrying schedule too, and it was wasted.

Big Andrei’s group practicing near base camp.

Us watching big Andrei’s group practicing. Just picture everyone wearing a mish mash of mountain clothes and sunglasses to protect against the intense glare off the glacier. Y, a strong climber from Kazakhstan, dragged a plank over and the four of us sat on it and watched and ate sunflower seeds. It’s actually quite hot during the day and the glacier has more texture, so it’s fine to wander around in flip flops or crocs as pictured here. I was so amused by our footwear hence this photo. A fond moment.

The dining tent at night. The perpetual balance of drinking a lot of fluids to help with acclimatization and not wanting to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night. For female climbers, the pee funnel has been a lifesaver. You can use it to urinate standing up or use it with a pee bottle for when it’s too cold, the weather too bad, or you just don’t want to walk far outside of camp at night.

Base camp at dusk. Except it gets extremely cold at night when the sun sets. So I usually ran to my sleeping bag and hopped in as fast as possible for a semi-sleepless night (because I’m a light sleeper and sleeping at altitude is never great). I’m impressed that they can even get semi-shitty wifi at base camp. It barely worked and we jokingly called it the nyet-work or inter-nyet, considering all the Russian climbers and Russian being the dominant language.

Fond moments at base camp. I love these. A Czech climber brought his clarinet to base camp and played for us. And people also sang. I love the mishmash of nationalities and languages and small moments like these. We were all resting at base camp after our first rotation and before a summit push. Natalya, an unguided solo climber from a small town in Russia was an interesting character (my mental nickname for her was the mountain elf). We couldn’t communicate in a common language, but she’d appear and disappear around base camp and the higher camps. She was at camp 1 and looked wrecked from whatever she had been up to on the higher slopes. I have a vivid image of her sorting out a hilarious mess of hair frizzed and tangled in all directions. But she was sweet and on the day of our departure I gave her the rest of my bag of Trader Joe’s trail mix (she was relying on food she had brought for every meal at base camp and above and was already quite skinny at that point), gave her a hug, and wished her good luck on her summit attempt. We’ll see how she fared. I have her WhatsApp number and sent her a garbled Google translated message in Russian.

It was always fun watching the helicopter come in. We also got to watch the helicopter arrive when we were at above 5000 masl.

View into Kazakhstan from camp 2 at about 5500 masl. A Czech climber reported that a tent blow away earlier in the season. And the winds up here are ferocious. You can hear it coming over the mountain and then it hits the tent and batters the walls. It’s hard to sleep in those conditions, along with the general difficulty with sleeping that accompanies altitude. I have to say that M was impressively good at sleeping. If only I had 10% of his ability, I’d be so much more well rested on these trips.

View of the route up to Chapayev Peak. Can you spot the small dots? Those are climbers on the route.

View from the traverse and into camp 2.

The sketchy traverse. The photo doesn’t do it justice because to the left it’s a long way down to camp 2 or into the massive crevasse. I didn’t spend too much time looking in that direction and just tried to avoid tripping while placing each foot into each footprint.

So many ropes to choose from. I also had issues with my Grivel ascender locking up randomly. It would operate smoothly for hours then all of a sudden I would have issues with it not budging. It sucked. I’ll use a different ascender next time. Also, we summitted Chapayev in white out conditions and had to descend in shitty conditions where any of the moisture on my gloves was frozen. I don’t have any pics of the summit because there was no view. But Y, the Kazakh climber, was up there with his tent and we shared candy and hot water and a quick rest in his tent before we descended. The ascent was 6 hours and the descent around 3 hours. Notably, on the way down, both M and I had a run-in with the crevasse that is right outside of camp 2. M went in and needed Arturo’s help to get out. My right leg punched through snow past the knee and I started tipping upside down, but was able to extricate my leg and continue descending. Except it freaked me out a bit and I wanted to get out of the crevasse terrain fast. I also ripped through 2 of my favorite and newer pairs of gloves on the descent from the heat/friction of rope against glove when rappeling.

Also, because we descended for several hours in snow and wind, it took me forever to warm up back at camp. I was happy to have my chemical warmers and cuddled one with my feet and dropped the other one in my shirt. Arturo also said they were useless because they rely on oxygen, but I haven’t had major issues with them in the past and like to throw one in my sleeping bag if it’s really cold.

Big Andrei’s climbers heading down from camp 2.

Descending from camp 2 to camp 1 the day after we summitted Chapayev Peak. At least I have another 6000er summit under my belt, and it was the most technical and most difficult one I’ve done. Anyway, this rocky area was interesting to descend because you have to traverse left or else go swinging right onto the rocks. And the tangle of ropes is chaotic, so you have to make sure to sort out your figure 8 device (for rappeling) your friction hitch (your safety backup to the figure 8 device that should halt an uncontrolled descent), and your carabiner on a sling (everything is on this sling in my setup, but the carabiner is at the end of the sling so I can attach it to fixed lines or above a knot or on a loop at transition points in the fixed lines). The biggest fear I had was fumbling and dropping my figure 8 device for rappeling. You can use a munter hitch or a combination of carabiners to rappel as well, but I have had butterfinger moments ice climbing and have dropped my ice axe, ice screws, and belay devices.

The baby crevasse near camp 1. M fell into a crevasse near camp 1 but Arturo was far ahead of him, so M had to extricate himself.

What our packs looked like after descending from camp 2 to camp 1, gathering more of our belongings, and then to the base of the mountain, where we had stashed things like our smaller boots. I’d say this was around 40-45 lbs. It sucked going uphill. Also, most people leave their trash up there. We packed down as much of our trash as possible, as seen on the top of my bag. It weighed a surprising amount.

My Petzl locking carabiner locked up. Not from me overlocking it, as some people might assume. It was locked but not too tight. And I got stuck descending the route from camp 2 to camp 1 when it wouldn’t unlock. I was hanging on the fixed rope for a good 15-20 minutes trying to unlock it. I rubbed it between my hands and I also basically stuck it in my mouth to try to see if it was frozen. Nope. We had to hammer it open with the adze of my ice axe. And when I suggested I should switch to a newer spare locking carabiner, Arturo said don’t bother. And then it locked up again. I swappled it out for a new one I picked up.

Reunion with Andrey Erokhin, a badass mountaineer and IFMGA guide from Kyrgyzstan. I had met him in 2021 via Nastiya, my guide on Pik Lenin. I had mentioned her earlier. He’s a great guide, super strong, and his team successfully summited Khan Tengri (although I heard that Andrey almost fell through a cornice around camp 3 [aka almost died]). Congrats to all the team members!!! Also funnily enough, the IFMGA guiding world is quite small and he’s friends with Ossy Freire, an IFMGA guide in Ecuador. Ossy and Andrey met on Manaslu in 2022. Ossy taught my mountaineering course in Ecuador in 2019, alongside my friend Juli, the first woman in LatAm to earn the IFMGA certification, via Mountain Madness. Juli will be in Bishkek in November for a general assembly meeting of the IFMGA. I connected the two of them so she can pick his brain about climbing out here. Also, shoutout to Juli for being the awesome mentor that she is. I was able to communicate some of my concerns about Arturo’s guiding via Garmin inReach mini and it helped me feel confident in my decision to call off a summit attempt. She also took me to the hospital in Italy last year after I broke my ankle.

Waiting for the helicopter with an avalanche all the way down the valley. Earlier in the season we saw a huge avalanche hit the valley floor from the same area. Overall, we heard avalanches going off every day and multiple times a day. The day before, I saw part of a serac collapse and it was an impressive sight. But it also reminds you how fragile and little you are as a human being in those environment.

The helicopter coming in to pick us up. By then I had had it with being around Arturo and just wanted to get back to civilization. But it’s always bittersweet leaving these places. My heart hurt and felt so full looking at the mountains recede behind us. These are beautiful and wild places that I’m lucky to have visited. I’ll be back in the Tien Shan and Pamirs ❤️.

Some of the views from the helicopter ride. Absolutely gorgeous.

High altitude can be rough. This tanline is something. M got burned so badly his face was a hot mess of blisters everywhere.

About the Guiding…

In terms of Arturo, our guide, I have a lot to say, so bear with me. I’ve climbed with local guides in various countries and with expedition companies like Jagged Globe, KE Adventure Travel, World Expeditions, G Adventure, and Mountain Madness. In recent years, I have tried to climb with IFMGA guides. Sometimes this is possible, sometimes business practices are less than ideal. Like the time I thought I hired an IFMGA guide in Argentina for Ojos del Salado. I had contacted the guide on Explore-Share but when I was on the ground for the climb, it had been subcontracted out to a local guide who completely sucked, but that’s a separate story that I wrote about elsewhere. In this case, I was trying Adventure Peaks for the first time. I had booked them for a climb in India in 2022 but I broke my ankle and had to move my deposit to 2023. Which is how I ended up with Arturo for this trip. I’d prefer climbing unguided or by hiring a private guide as I did the first time in Kyrgyzstan and I learned my lesson.

As a note, I know that expeditions in Central Asia are a whole other level of dumpster fire. Poor communication and a different and harder culture are common here. There are far fewer resources available as well, like helicopters. In Nepal you can hop in one on short notice and for a decent price. Here, good luck if you need to be evacuated. What I am unhappy about is the quality of the guiding for the money we paid.

1. SEXIST

From the get go, he made disparaging remarks about women's empowerment. And when new climbers arrived at base camp, our guide joked about men flocking to talk to me. When I jokingly said that no one looked good in the mountains, he muttered "don't flatter yourself" and "there are slim pickings." Yet during the day he commented on and leered at the new women climbers at base camp like a disgusting pig. He even commented on how he was glad he was wearing sunglasses so no one could tell what he was looking at.

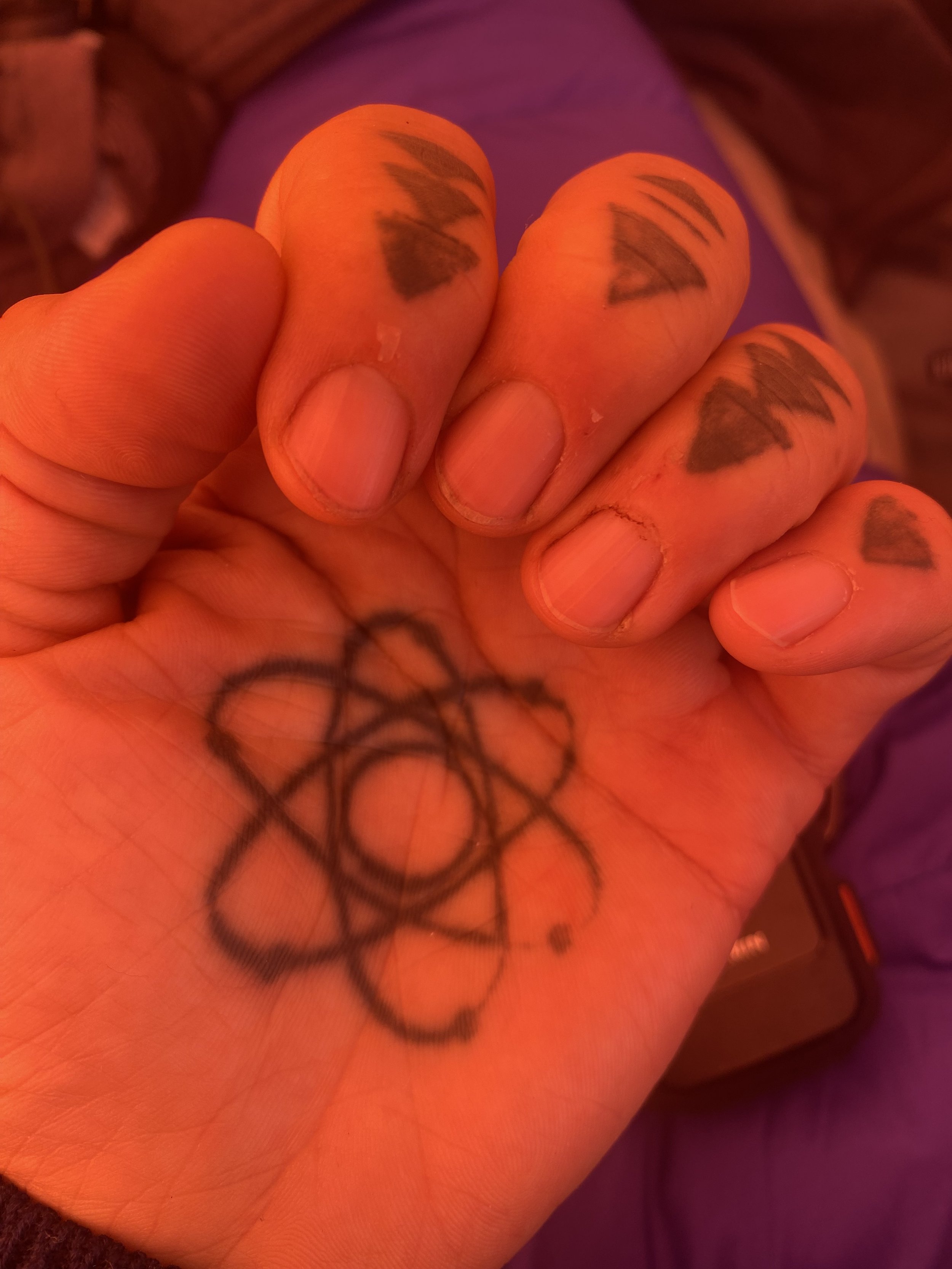

Here I’ll make the disclosure that I’m queer, have predominantly dated women, and my flirting skills are abysmal. And I also have a tattoo bodysuit and scarification work. So I’d say Arturo’s attempt to characterize me as a vain woman were way off the mark. I’ve had people tell me that I’ve mutilated myself. Never have I been told I’ve been vain in an attempt to solicit attention from men at base camp. My mom would be thrilled if that were the case.

And I’ll also highlight the fact that the international mountaineering community is unwelcoming and potentially dangerous for queer and trans climbers. It’s why I have never met an openly out queer or trans person in my international adventures. It’s also why younger queer and trans climbers I’ve met in the US are afraid to travel abroad for these types of climbing trips.

Arturo would also repeatedly make comments like “women and their need to be clean” etc. when I “showered” at base camp (twice in 2 weeks) or when I did things like trim my nails. Or he commented that I was just as vain as the Kyrgyz women climbers (who had lip fillers etc) when I applied ointment on my cuticles, knowing that they tend to rip and bleed at altitude.

The state of my cuticles at camp 2.

2. POOR DECISION MAKING AND ORGANIZATION THAT COMPROMISED ACCLIMATIZATION AND SAFETY

We didn't pack and plan appropriately to carry gear/food/fuel up to camp 1. Instead, we ended up caching items about 100-150 meters below camp 1 and then descended to the base to camp for the night. All other teams went from camp to camp as planned, not partway up to camps. We were the only team that did that.

Importantly, our guide chose an avalanche debris field (see below). And when my climbing partner asked if it would slide again, he was answered dismissively. Yet within 30 minutes, and while Arturo’s back was turned, I watched another small avalanche slide over where we had cached items. When we went back up the next day, we saw that we lost food, fuel, and equipment, and it compromised our rotation, therefore we couldn't go up to camp 2 as the next step in acclimatization. We only went halfway up.

The avalanche debris field where Arturo thought it would be a good idea to cache gear/food/fuel. I can say that Juli and Ossy and Andrey and Nastiya wouldn’t have cached gear here because duh, it’s an avalanche debris field.

Later in the trip and during our alleged summit push, Arturo told us that we should just attempt Chapayev Peak because we were too inexperienced and too slow to try to summit Khan Tengri and he didn’t want to be responsible for us for a long summit day. Why is he even a guide if he doesn’t want to do the work? Anyway, we were okay with this decision knowing that our whole trip was questionable because of what happened in Tajikistan. But then he decided to tell base camp that we'd go to camp 3 and try for the summit and M and I only found out because we overheard his radio conversation with base camp. When he informed us that we were going to camp 3 for three days, he also said that our return would be via camp 3 to camp 1 (red flag for me - that would be a huge day of ascending 300 meters and descending 1600 meters after a summit attempt. A rough calculation would be about 8-10 hours to ascend and descend that route, probably more when factoring in exhaustion from a summit/summit attempt). The next day, when I told him I didn't feel comfortable with the proposed plan and the plan to descend from camp 3 to camp 1, he also denied saying that was the plan. He also didn’t agree with me suggesting I descend with big Andrei’s group (and he later pointed out that the group descended in 6 hours vs our 8 hours, suggesting I wouldn’t have been able to keep up with them). He also yelled at us about a slow descent the day we went halfway up to camp 2 but he had us descend with an ascender and friction hitch on the fixed rope, which was painfully slow and awkward. I was also okay with Arturo and M going for a summit attempt. M was a great teammate and listened to my concerns and was okay with me calling it off. We also had maybe 1500 calories per day per person. And we only had about three days worth of food and no additional meals at camp 2, which would have forced us to descend to camp 1 exhausted, which increases the danger component exponentially.

It also turned out that Andrey E’s group needed to wait at camp 3 for five days to summit. We were due to go up to camp 3 a day after Andrey E’s group, which meant we would have been up there for at least four days. Andrey’s group had planned accordingly and had enough food. I wasn’t even sure if we would have had enough fuel to melt snow for water. So in the end, me calling off a summit attempt was probably a good thing. Additionally, Andrey E made the smart decision that his group would descend the south side. It’s safer from a descent and exhaustion perspective and you don’t have to re-ascend Chapayev Peak as part of the process.

3. POOR COMMUNICATION SKILLS

He was passive-aggressive but claimed he was "just joking" all the time. One day he'd say don't worry about going slow because we're carrying loads up to camp (within the average time window) then the next day he'd say we were so slow because look how fast the other team was (they were also acclimatized and carrying less gear; admittedly they were also a strong and experienced group).

He also said Adventure Peaks would want clients to descend with a friction hitch and carabiner on a sling clipped in to the fixed rope for safety and liability reasons. This adds time. Then he pointed out that we descended so much slower compared to other teams that descended Sherpa style (without a friction hitch and with just a carabiner on a sling clipped into the fixed line). It took us about 8 hours from camp 2 to the base of the mountain vs 6 hours, and during that 8 hours, we took a long break at camp 1. He also descended far ahead of us so he barely had visual contact with us and didn't see when my climbing partner fell in a crevasse and had to extricate himself, and then made disparaging remarks to my climbing partner (a pattern for the entire trip). For example, he could have designated tasks for us, like getting snow for melting water. When I got a full bag of snow and brought it to him, he sarcastically said wow, great job. When M got more snow for water, he told M something along the lines of that was the most useful he’d been all expedition.

This pattern of passive aggressive insults also continued off the mountain like when we went to dinner with some guys from the World Expeditions group that were picked up on the south side of Khan Tengri. M is a bit on the spectrum side and has wide and varied interest and nerds out about things. I’ll sometimes chime in if something catches my interest. During such a moment during dinner conversation, I heard Arturo mutter to one of the other guys, can you imagine being stuck on a mountain with these two, no wonder why we quit. No, I called it off because he had demonstrated piss poor decision making, communication, and planning skills that I thought would endanger our safety and well-being. Along with the fact that this man said he didn’t want to guide us if we had a 20 hour summit attempt. The number of times he snapped at or insulted M was disgusting. While M was fine with it, I don’t think this is okay. Expeditions can be stressful and team meltdowns are a thing when people don’t get along. And it can endanger folks. Maintaining a harmonious and fun atmosphere offsets some of the pain and suffering you experience up there.

He also spent time shit talking us to other clients on other teams. I was not a fan. Here I’ll say that M and I were not what I would consider difficult clients. We rolled with Arturo’s waffling and didn’t complain. We also didn’t push to go faster or harder or higher or demand we try the summit.

4. POOR SAFETY PRACTICES

At one point, I had problems with my ascender and we switched ascenders. While Arturo was putting me on his ascender, he accidentally and very briefly disengaged the cam from the rope entirely. I had no backup carabiner on the rope and was just holding on to the rope with my hand and my feet were on the rock. That could have been a bad oops moment.

Arturo also insisted I use his Blue Water 60 cm slings that were girth hitched together rather than use my BD 120 cm Dynex sling. His Blue Water slings were from 2007. It’s generally accepted that soft materials like slings be replaced every 5-10 years. I had no idea how much wear and tear his slings had seen and I used my 2022 sling, which he repeatedly commented on. This is the material that you’re relying on for rappeling and for clipping in to the fixed line….if this fails, you’re off the mountain and likely dead.

5. POOR KNOWLEDGE OF THE ROUTE

Whenever he was asked about the route or time, he would say he didn’t know and couldn’t estimate. It’s not like people haven’t been on this mountain. He was just too lazy to find out and communicate with us. In fact, Sergey had said that carrying a load from camp 1 to camp 2 would take about 8-9 hours. On our carry day up to camp 2, that was around the time that we took. Yet we were “too slow” compared with an acclimatized Andrey E’s group, who also weren’t carrying a substantial load up that day.

6. MESSING WITH OTHER CLIMBERS

Arturo also messed with another climber’s head. In conversation with us and out of earshot of this climber, he called him a Ken doll who had no business being on the mountain. See below screenshot of the conversation I had with O after we both got back to Bishkek.

Screen shot of a conversation I had with O, who was with big Andrei’s group. They had to share a tent at base camp. I also showed this to Juli, who was surprised that Arturo was saying this kind of shit to another guide’s client.

7. QUESTIONABLE CERTIFICATION

Arturo has been guiding for 30+ years. It doesn’t show based on his lack of professionalism. He also repeatedly poo pooed IFMGA certification. Meanwhile his certification isn’t recognized by professional guiding associations, as per my conversation with Juli. He allegedly gained certification through the Plas-y-Brenin National Mountain Centre. The UK certification is somewhat confusing to me so I wasn’t sure what this meant aside from he wasn’t IFMGA certified. Also, we received this information less than a month before our trip and well after we had paid for our trip. As well, I made the mistake of assuming an international expeditions operator would hire appropriately certified guides. And I assumed that the fact that Andrew had climbed with Adventure Peaks for over a decade meant that there was an acceptable level of quality. I was wrong.

Summary

This was a less than ideal experience with a guide. I wasn’t necessarily expecting a summit on Khan Tengri because of our snafus in Tajikistan, but I was expecting better guiding. On the plus side, I’ve consolidated and gained confidence in my skills. And I’d like to tackle this mountain again, either alone and unguided, private guided, or private guided with friends and no time limit so we can sit out bad weather windows etc. And I think the best plan is to book tents at each camp through Ak-Sai and ascend via the north and descend via the south for safety. I’ll be back, Kyrgyzstan!

Peak Lenin, Kyrgyzstan, 2021

Kyrgyzstan, and the countries in that region of the world in general, have been on my list of places to visit for 4-5 years. After a 2 year wait, the climbing trip was a go. We were supposed to climb Khan Tengri but we changed our plans for a variety of reasons and ended up on Pik Lenin, more recently renamed Ibn Sina. This is one of the five Snow Leopard peaks - aka the five 7000-meter mountains in the former USSR, for which mountaineers would be awarded a medal to recognize their achievement. The other four are Ismoil Somoni (Tajikistan), Jengish Chokusu (formerly and still referred to as Pobeda - the most dangerous of the five; on the border of Kyrgyzstan and China), Peak Korzhenevskaya (Tajikistan), and Khan Tengri (on the border of China, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan).

Culturally, I found Kyrgyzstan interesting. It’s a region of the world where I look like I could be a local. People spoke to me in Russian or Kyrgyz more often than not, until they figured out that I was an ABC (American Born Chinese). There are not that many English language books that delve into the history of the region, which is unfortunate, as it was part of the historical Silk Road. But you can see the influence of the former USSR on the region, although the architecture is less brutal and soulless than the Soviet architecture in Mongolia. And don’t forget that Kyrgyzstan is one of the youngest nations, coming into being in 1991. Which means they’ve also had to create their own national mythology, with Manas, serving the role.

In terms of opportunities to climb, ski, hike, etc, Kyrgyzstan is amazing. It’s gorgeous. The mountain ranges are huge and cover most of the country. And the mountaineering feels very Soviet style. Hard to explain it, but the guides and attitude are what you’d think of if you thought of Russians leading expeditions with hard-nosed and unsentimental, but capable and strong guides. Unfortunately, in terms of success, I was unable to summit Ibn Sbn Sina - we were forced to turn around around 6700 masl during our summit attempt because I lost vision in my right eye and we had to descend to about 4350 to Camp 1. During the descent, my eyesight recovered, so turning around was the correct decision. During follow-up at an eye clinic in Kiev, no problems were found, but the history of PRK (corrective eye surgery) may have played a role, although anecdotal reports of similar vision problems have been reported in people who underwent the surgery and climbed within a few weeks to months of the procedure rather than 14 years later, in my case. Who knows. Shit happens. You adjust. I’ll try a 7000 meter mountain again. Where is TBD - Tajikistan and India look intriguing.

Bolivia, 2021

Huayna Potosi (6088 masl) summit via normal route

First time I tracked my calorie count on a summit day. I knew it would be a lot, but I don’t think I was expecting it to be 6000 for a 12-hour day on a 6088 masl mountain.

Huayna Potosi about (5900 masl) no summit due to conditions on the French route

Sunrise from the French Route. This was my second time on the mountain in 8 days and my third time overall. First time on the French Route. It has many more crevasses to bypass and we stopped at a small slab avalanche - other climbers had gotten caught in it and I believe someone suffered a leg injury. I opted not to try for the summit from that point because it didn’t look like it was in fantastic condition and I was using this outing as a training run for Kyrgyzstan.

Condoriri summit via AD+ route

Summit of Cabeza de Condoriri

Smiles from 18,530 feet above sea level. The ridge on the way to the summit was fear inducing, but the satisfaction of summiting can’t be beat.

Cabeza de Condoriri from the approach. We descended along the glacier to the right, although there were several rappels. And it turned into a 13- hour day.

Tarija summit instead of Pequeño Alpamayo because I was too tired from a 13-hour day on Condoriri the day before.

Absolutely gorgeous view of Pequeno Alpamayo from Tarija. I had been scheduled to climb this soon after Condoriri, but I thought I had a day to recuperate between the two. My misunderstanding and I felt too exhausted to tackle the more technical climb. Plus I wasn’t happy with the gear I had brought - more general mountaineering crampons when I would have preferred my Petzl Darts that I use for strict ice climbing. I’ll be back to climb this in 2023 and probably a trip down to Peru for the July-August climbing season.

Ecuador, 2020

Summit on Carihuairazo

No summit on Politecnica because we got caught in a bad storm and bailed.

Weather conditions on El Altar were not great for the other days we were looking at.

First time mountain biking at altitude and I thought my heart was going to explode, but it was fun because we went with friends.

Pico de Orizaba (5636 masl), January 2020

Last bit to the summit. First view of the crater rim

Dawn

Summit cross

Mexico is a fantastic, colorful, cultural, and historical gem. We had so much fun and ate so much food. Pico de Orizaba is the third highest mountain in North America and tends to be icy, more than snowy. Aside from The Labyrinth (of rocks), it seems like the actual climb is fairly straightforward - up, up, up and switchbacks. It was quite windy at the summit with my fingers freezing within seconds of taking them out of the gloves to take pictures. We didn’t stay long because of the wind and then a bit of a white out descended on us on the way down.

This was a fun trip because J and D, two guide friends from Ecuador, were able to join us, relax, and have fun, with no worries about the route, the itinerary, or having a client tied to them. It was cool seeing how fast they were able to ascend on their own.

Ojos del Salado (6863 masl), Argentina, 2019

Summit selfie after dry heaving from low blood sugar. I was worried it was altitude sickness but felt okay otherwise

View of Ojos del Salado from Arenal camp. Our water source was melting glacial water

Clouds over Medusa from camp at Arenal, a 7 hour drive from the road

View into Chile from the summit of Ojos del Salado

The summit markers on Ojos del Salado

Ojos del Salado is the highest volcano in the world at 6863 meters above sea level. It’s in the Catamarca Seismiles region, Seismiles referring to the plethora of 6000 meter+ mountains in the region. I’d like to revisit this region and climb more of them at some point.

Ojos del Salado is a pretty straightforward mountain. We went from the Argentinean side and got a ride to camp at Arenal. A ride that takes 7-8 hours navigating rocky and relatively unmarked terrain. The other option is walking in from the road for 5 days, if you have the time. Water may also be harder to find on the walk in. The more popular option is to go from the Chilean side.

While the mountain was fantastic, the guiding was a far cry from the level of guiding I saw from IFMGA guides in Ecuador. I had an Argentinean guide qualified through the Argentinean association. Main complaints? He couldn’t give me a rough estimate of time from the higher camp to the summit. He walked 100-300 feet ahead of me so his pacing was nonexistent. He didn’t communicate the itinerary well. His cooking was still subpar. His decision making was really complete shit. The day we moved from Arenal to base camp (about 500 meters altitude gain), we left late in the morning and got to base camp around noon. Then he suggested we try for a summit bid. At 13:00. I’m not that fast and he didn’t know the route and it was too late in the day. I have never been with a guide who would have made that suggestion. Then we got somewhat lost on the way up through the first slope to the plateau so we turned back after wasting 4 hours. He went straight to the tent where he was silent and sullen in his sleeping bag. I cooked us dinner. He didn’t even tell me when we would wake up for the summit bid the next day.

The next morning, he wasn’t even awake by 7:00 am. Based on my past experience on other mountains, I know I can ascend 1000 meters on mountains 5000-6000 masl in 5-8 hours. At altitudes above 6000 masl, I figured I’d be a few hours slower so I made the assumption that it’d take me 12 hours and if I wanted to get back before dusk, I had to leave by 7:00 am or so. I ended up leaving before my guide. And I didn’t have any breakfast because he had the lighter so I couldn’t make myself anything. I have never done that. I took myself up the first part of the route and up to the plateau where he caught up to me. Then close to the summit, he said we might have to turn around because it was getting too late. So I sat down in frustration and thought that was it. I also bonked super hard because of lack of calories and insufficient food and water on me. Then he started moving up the summit again. Which he didn’t communicate to me. So in the end, I summitted, but I was furious with him. It was a less than optimal experience.

Nevado San Francisco (6016 masl), Argentina, 2019

High altitude sunrises are the prettiest

Sunrise about 1-2 hours into our ascent of Nevado San Francisco

Summit with a view of Incahuasi (there are Incan ruins on Incahusi)

Summit notebook

The Argentina trip involved a not so great guide. Here he forgot the paperwork that would allow us to take the car past the army checkpoint at Las Grutas. This meant he had to bum a ride from another climber to get us to and from this mountain, about 20 minutes away by car from the refugio. My guide also wasn’t aware of the setup at Las Grutas and brought only the most basic of food. He “cooked” twice in the 4 days we were there so we had pizza for most meals. The other time that he “cooked’ was after coming back from this mountain - it was a mix of rice, canned vegetables, and tuna. After a 12 hour day. It was disgusting and unappetizing and I went to bed hungry. Meanwhile, other teams had steak, burgers, stir fry, sandwiches, eggs, etc. A Polish high altitude scuba diver gave me some snacks and a French climber gave me a ready to eat meal because they felt bad for me. I’m not really sure what my money paid for because this was a guide who also told me I could wear hiking boots on a 6000 meter mountain when I’ve never worn hiking boots on something that high. And good thing I listened to my own advice and wore my double boots because it was very cold for a few hours of the climb and I would have had foot problems if I had worn my regular boots. He also failed to do a gear check before we left, but having just come from a climbing course in Ecuador, I had packed my gear appropriately and wasn’t at risk for hypothermia or frostbite. If someone with less experience had done this trip with him, I think he would have had more problems.

The mountain itself? Super nice and easy. It’s got a long and meandering route up to the summit, which is not so hard to find. There was one tiring part on a very long traverse, but it wasn’t a sketchy traverse like on other mountains. I had fun on this one and my acclimatization felt great.

Cotopaxi (5897 masl), Ecuador, 2019

Up, up, up in the dark

Shadow of the mountain at dawn

The crater - Cotopaxi is an active volcano and was closed to climbing for several years.

Fixing a crampon on the last snow ramp to the summit

On our way down in a little bit of wind

Summit selfies are the best and worst. L to R, me, David, Kate

Gorgeous glacier

During our course in Ecuador, we were scheduled to climb three mountains. Cayambe, Cotopaxi, and Chimborazo. In the mountains, you have to accept that you have zero control over the weather. With that in mind, you also have to make good decisions for your safety. The first time we were supposed to climb Cotopaxi, we changed plans and stayed in Tambopaxi because the snow pack was too unstable and a large slab avalanche had been triggered by climbers the night before. A few teams tried to summit the next night but all teams turned around due to the high risk. So we set our sights on Chimborazo but over the course of a day or two, the snow pack on Cotopaxi stabilized and the weather on Chimborazo got worse and the risk of avalanche increased. We took an unanimous vote to try Cotopaxi and it was a great choice as almost the entire team summitted. The weather conditions weren’t the greatest on our summit push, though. There were medium winds that scoured our faces with ice crystals and the last hour or two before the summit was challenging with very loose and deep snow that was exhausting to swim through. There was also a long traverse and if you’ve never been on the mountain, one wonders what’s on each side of you in the dark - steep slopes and crevasses that you can fall into (a foreign climber had fallen into a crevasse on Cotopaxi a few weeks earlier - she died and two additional climbers were injured). I just remember repeating the mantra - don’t catch your crampons in your pants and fall. Small mistakes at altitude can have serious consequences. And your mind and even simple things get much harder with less and less oxygen.

Cayambe (5790 masl), Ecuador, 2019

Last 20-30 minutes before the summit

Whiteout conditions on the summit of Cayambe

Close to the summit near a gigantic glacier

Spot the climbers

This was also a great climb. I joined up with a Mountain Madness group to refresh and learn new skills (prussiks, knots, crevasse rescue, self rescue, etc), as well as climb some of the fantastic mountains in Ecuador with new and old friends. I think this was an 11 hour summit day. We left around midnight or 1 am and made it up to the summit after sunrise. Unfortunately we had whiteout conditions at the summit, so we didn’t have a great view, but the glaciers were absolutely fantastic. Also, keep in mind that this mountain has a few false summits, so climber beware. There’s nothing more vivid than the squeak of your ice axe in the snow, the sound of your breathing, the rope in the light of your headlamp, and the crunch of your crampons in the snow. Your reality becomes so small and so present, there really isn’t anything like it. You have to remember to eat, to hydrate, to layer up even though you’re pretty cold the whole time. But the joy of being out there with nothing else weighing on you, it’s why I keep on chasing these mountains.

Illiniza Sur (5263 masl), Ecuador, 2019

This is a great AD level climb in Ecuador. You can do it over 2 days, or you can stay at the refugio for another night and climb both Illiniza Sur and Illiniza Norte. I wanted slightly more technical experience with steep snow slopes of 70 degrees in some areas. We had fantastic weather and the climbing conditions were perfect. We made it in time to see a fantastic sunrise with Cotopaxi in the distance.

Aconcagua, Argentina, 2018/2019

Camp 2 ~5000 masl

Plaza de Mulas ~4300 masl

Argentina, 2018/2019. We made it up to camp 3 but we didn’t have a weather window to attempt a summit. Our actual summit day was scuttered by winds of up to 50 mph, which means the wind chill at 6000+ meters above sea level would have been brutal. A good reminder that we’re only human and the weather will do what it will do.

Huayna Potosi (6088 masl), Bolivia, 2018

Base camp ~5000 masl

Huayna Potosi, 6088 masl

Quickie weekend trip to Huayna Potosi in Bolivia. What a nice climb. You can do the normal route in 2-3 days. I did it in 2 days, which actually amounts to a 24-hour period. You drive to first hut, then you hike up to the base camp (about 2 hours), then relax until around midnight, then you head for the summit with the goal of arriving around sunrise, then a few hours down to base camp, eat and get your stuff, then an hour down to exit the park. Bolivia is great for accessible 6000 meter peaks!

Pico Austria (5328 masl), Bolivia, 2018

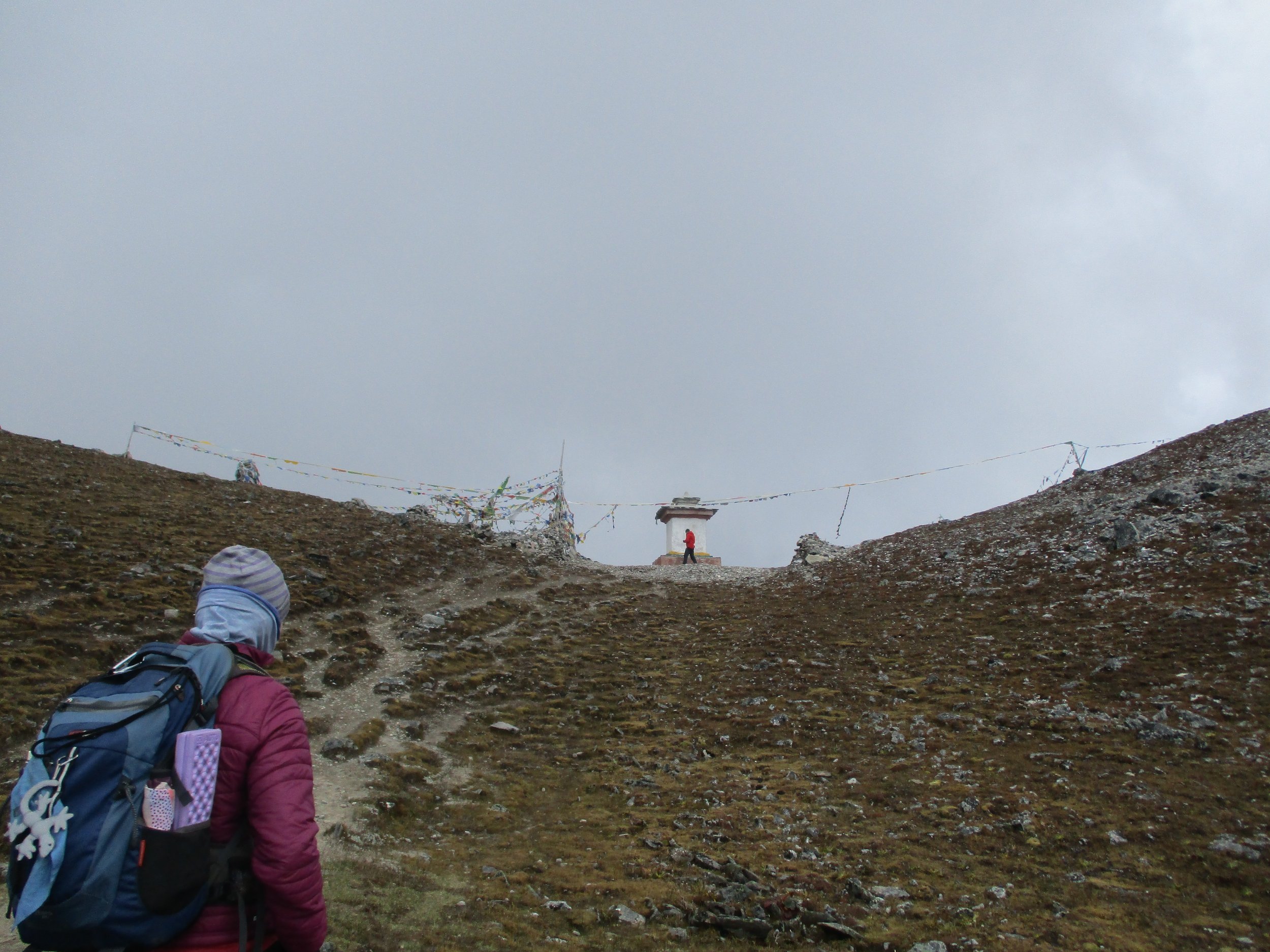

Bhutan Snowman Trek, 2018

Aconcagua (La Cueva ~6650 masl), 2017

Mera Peak (6461 masl - central peak), 2016

Flying into Lukla is truly an experience. The approach between the mountains, the short runway at an angle, and a cliff at one end and a wall at the other end mean it’s an interesting flight.